States Provide Communities with Environmental Justice Alternatives In Lieu of Federal Legislation

- The following is the opinion and analysis of the writer.

- Use of this article or any portions thereof requires written permission of the author.

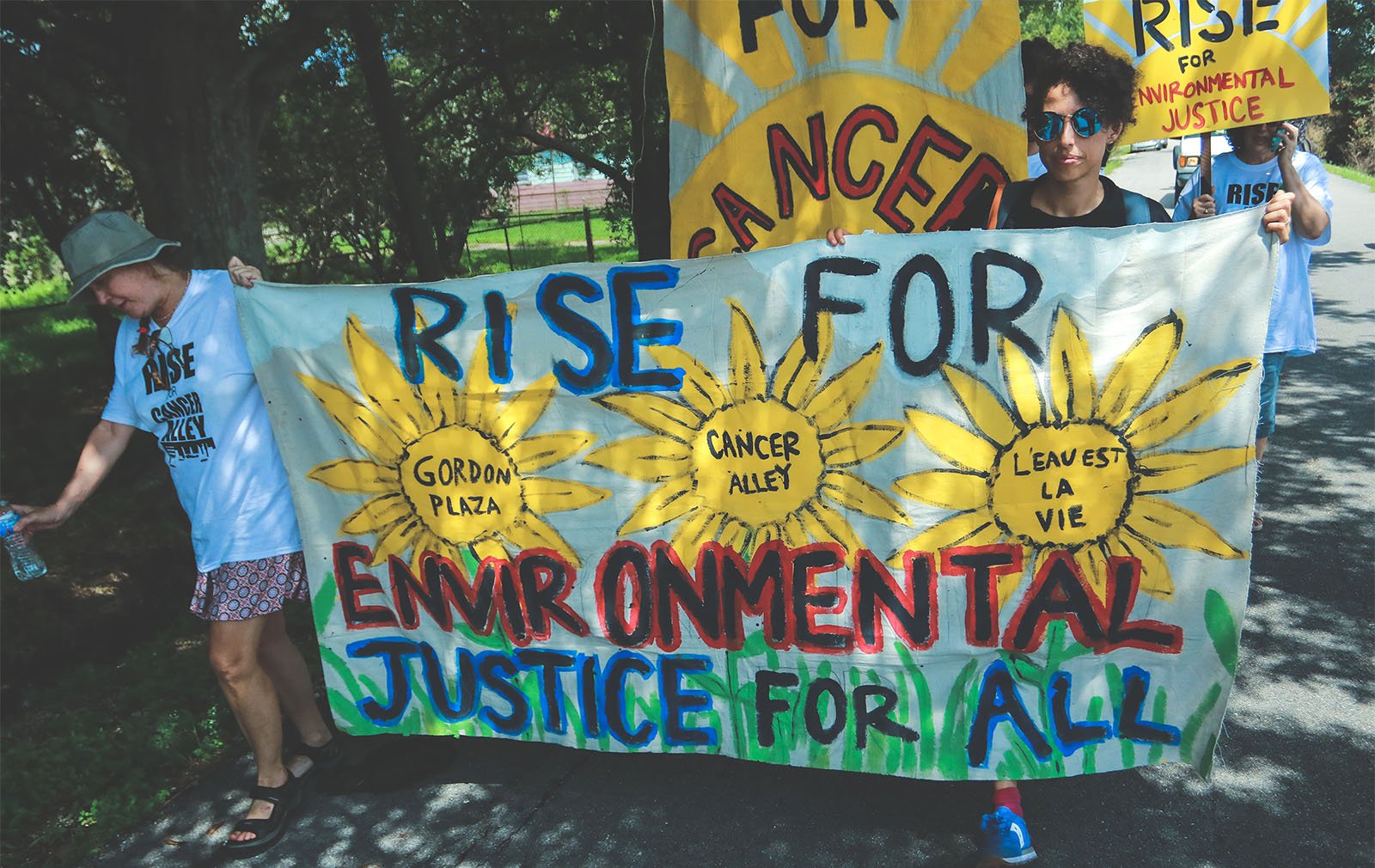

webRNS-Environmental-Justice1.jpg

Environmental justice, or the question of unequal distribution of benefits and burdens across certain communities, has become a focus of many politicians in recent years. Last month, Representative Raúl Grijalva, the U.S. Representative for Arizona’s 7th Congressional District, re-introduced the A. Donald McEachin Environmental Justice for All Act.[1] The bill sets more stringent guidelines for federal agencies on projects that might negatively impact vulnerable communities.[2] Although the legislation would be a useful advocacy tool for communities, its likelihood of success is questionable; Rep. Grijalva introduced similar bills in 2020 and 2021, but neither bill went to a vote in the House. Without such federal legislation, state legislatures have considered their own environmental justice statutes, often using input from affected communities.

In the western United States, five states – Washington, Oregon, California, Colorado, and New Mexico – have successfully passed environmental justice statutes.[3] Texas and Arizona have proposed bills addressing environmental justice, but the bills were not successful.[4] These statutes range from establishing environmental justice task forces to requiring more extensive reviews of environmental impacts on vulnerable communities. States often have their own definition of a vulnerable or affected community, but most involve socioeconomic, demographic, and public health data.[5] To ensure that both community and business needs are considered, task forces typically include members of prominent economic sectors as well as community organizations. Although Colorado’s statute simply establishes an environmental justice task force without enforcement power, [6] other states have supplemented these task forces with more rigid requirements and enforcement authority.[7]

To prioritize the needs of affected communities, Washington made sure to first establish an Environmental Justice Task Force before passing enforceable acts on environmental justice. Washington also passed the Healthy Environment for All (HEAL) Act in conjunction with the Climate Commitment Act to increase enforceability of environmental justice considerations.[9] The Task Force met regularly with community groups and businesses before providing recommendations that were incorporated into the HEAL and Climate Commitment acts.[8] The HEAL Act created an Environmental Justice Council and established a benchmark for state agencies to meet regarding expenditures and investments that go to affected communities. The Climate Commitment Act created a greenhouse gas emissions cap-and-invest program with a focus on data collection to eventually establish stricter emissions standards that protect air quality of affected communities.[10]

New Mexico was one of the first states to establish an environmental justice task force, prioritizing immediate institutional support over extensive community input.[11] In 2005, Governor Bill Richardson signed the Environmental Justice Executive Order, which acknowledged the existence of environmental justice concerns and proposed executive solutions.[12] Those solutions included requiring departments and commissions to use available data to address impacts in low-income communities and communities of color when assessing project proposals.[13] Further, the EO created the Environmental Justice Task Force, a multi-agency task force that served as an advisory body, making recommendations to state agencies and developing policies that address environmental justice issues in low-income communities and communities of color.[14] However, the EO explicitly states that it does not create a private right of action to enforce any provisions within the order.[15]

Like New Mexico, some states passed legislation before fully understanding community needs, but then they went one step further to amend or propose new legislation years later. For example, the Oregon legislature passed an environmental justice law in 2008, not long after New Mexico. In 2022, the Oregon legislature revised the law to provide more governmental support.[16] The revised statutes created an Environmental Justice Council to replace the 2008 Environmental Justice Task Force and increased the staff and funding for projects.[17] California also expanded some of its environmental justice statutes, which were initially passed in 2017 and 2018.[18] A statute passed in 2017 established the Community Air Protection Program, which had the goal of including communities in the regulatory process to improve air quality for low-income communities.[19] However, like the critiques of many of these state statutes, some communities believe that the law has not been successful because it does not lead to improved pollution controls or increased funding for projects.[20] In May 2022, the California Environmental Protection Agency was required to update its mapping tools, pursuant to a revised Senate Bill that also granted additional funding to projects benefitting low-income communities.[21]

Along with building a foundation for environmental justice work within state governments, these statutes can also provide a legal basis for citizen enforcement.[22] Citizens and advocacy groups in the East have pursued lawsuits requesting agency enforcement of environmental justice statutes where states have approved projects that exacerbate environmental burdens in affected communities.[23] A few of these suits have been successful, ending development projects that would have caused harm to already vulnerable communities.[24] In western states with actionable environmental justice statutes, citizens may also sue to urge enforcement.

States can pass bills that account for specific community needs in different ways. Whether a state includes affected communities in the creation of the bill, or amends it later to better reflect current needs, such bills provide institutional support for consideration of environmental justice. Importantly, these bills can also sometimes provide legal causes of action if environmental justice has not been considered in a state agency review. While federal environmental justice bills remain in limbo, states can create their own processes that provide consistency for business while also centering community needs.

[1] H.R. 1705, 118th Cong. (2023).

[2] Paola Rodriguez, Rep. Raúl Grijalva reintroduces newly named Environmental Justice for All Act, AZPM (March 23, 2023), https://news.azpm.org/p/newsc/2023/3/23/215370-rep-raul-grijalva-reintroduces-newly-named-environmental-justice-act-for-all-act/.

[3] Abby Blocker, State Trends in Environmental Justice Legislation, Waste 360 (June 8, 2021), https://www.waste360.com/legislation-regulation/state-trends-environmental-justice-legislation.

[4]H.B. No. 714, 87th Leg., Reg. Sess. (Tx. 2021); S.B. 1438, 53rd Leg., 2nd Reg. Sess. (Az. 2018).

[5] US Environmental Protection Agency, DWSRF Disadvantaged Community Definitions: A Reference for States, EPA 810-R-22-002 (Revised Oct. 2022).

[6] Colo. Rev. Stat. § 25-2-133.

[7] See generally Oregon Rev. Stat. § 182.536; Oregon Rev. Stat. § 757.747; Oregon HB 4077; Rev. Code of Washington 70A.02.

[8] Washington State Dep’t of Health, Environmental Justice, https://doh.wa.gov/community-and-environment/health-equity/environmental-justice#:~:text=The%20passage%20of%20the%20Healthy,agency%20approach%20to%20environmental%20justice (last visited April 30, 2023).

[9] Andrea Wortzel, Viktoriia De Las Casas, Shawn O’Brien, & Emily Guillaume, Washington Adopts Two Ambitious Environmental Justice Laws, Environmental Law and Policy Monitor (May 26, 2021), https://www.environmentallawandpolicy.com/2021/05/washington-adopts-two-ambitious-environmental-justice-laws/.

[10] SB 5126, 67th Legislature, 2021 Reg. Sess. (Wa. 2021).

[11] Exec. Order No. 2005-056 (N.M. 2005).

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Oregon Rev. Stat. § 182.536; Oregon Rev. Stat. § 757.747; Oregon HB 4077.

[17] Tracy Loew, Environment bills address Oregon’s bottle bill, earthquake safety, more, Statesman Journal (March 9, 2022) https://www.statesmanjournal.com/story/news/2022/03/10/which-environmental-bills-passed-the-oregon-legislature/65063333007/.

[18] California Code § 65040.12; AB 617.

[19] Rachel Becker, Has California’s landmark law cleaned communities’ dirty air? Cal Matters (Jan. 31, 2022), https://calmatters.org/environment/2022/01/california-air-quality-environmental-justice-law/.

[20] Id.

[21] CalEPA, Final Designation of Disadvantaged Communities Pursuant to Senate Bill 535, May 2022, https://calepa.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2022/05/Updated-Disadvantaged-Communities-Designation-DAC-May-2022-Eng.a.hp_-1.pdf.

[22] Andrea Wortzel & Viktoriia De Las Casas, State Laws Provide New Pathways for Environmental Justice Claims. 36 Natural Resources & Env’t 1, Summer 2021.

[23] See Friends of Buckingham v. State Air Pollution Control Board, 947 F.3d 68 (4th Cir. 2020); Town of Weymouth v. Mass. Dep’t of Env’t Prot., 961 F.3d 34 (1st Cir. 2020).

[24] Id.