The San Pedro River, Subflow, and Development

- The following is the opinion and analysis of the writer.

- Use of this article or any portions thereof requires written permission of the author.

San_Pedro_Riparian_NCA_3.jpg

Quantification of Federal Reserved Water Rights Necessary to Rescue the San Pedro

The Santa Cruz River runs through Tucson, Arizona. At one time, there were abundant flows of water in the Santa Cruz, but now the riverbed is usually dry. After years of groundwater pumping in the Santa Cruz Valley, the perennial flows of the river stopped in the mid-20th century, vegetation along the banks of the river died, wildlife disappeared, and now, water only flows in response to precipitation events. My concern is that this may also be the fate of the San Pedro River, one valley over to the east.

I first became interested in the San Pedro River as an undergraduate student studying environmental science at the University of Arizona. In one course, our instructor took us on a field trip to Cascabel, Arizona to meet people, living in a community, who were doing things differently—living more sustainability with solar energy, composting toilets, and rainwater harvesting features. Also on this trip, I discovered that if you drive due east of Tucson, you will come upon a luscious riparian zone, with green trees and water, the San Pedro River. How incredible!

Congress must have thought so too, because in 1988 Congress created the San Pedro Riparian Natural Conservation Area (SPRNCA) and expressly reserved water to protect the riparian area: “Congress reserves for the purposes of this reservation, a quantity of water sufficient to fulfill the purposes of the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area.” Also, Congress directed the Secretary of the Interior to file a claim to quantify the federal reserved water right in SPRNCA in the appropriate adjudication—the Gila River General Stream Adjudication (GSA). The purpose of the Gila River GSA is to formally review—that is, “determine the extent [i.e., quantity] and priority”—all of the water claims in the Gila River system. The Gila River adjudication started in 1974, and because of the number of claims and resulting complexity, it continues to this day. Consequently, the exact quantity of water rights reserved for SPRNCA has not yet been determined by the GSA. Meanwhile, building developments have been proposed in the areas surrounding the San Pedro River that pump groundwater as their main water supply. For example, some proposed developments in Sierra Vista are just five miles from the San Pedro River. Groundwater pumping in Sierra Vista certainly impacts surface water flows in the San Pedro River because of the interconnectedness of surface water and groundwater.

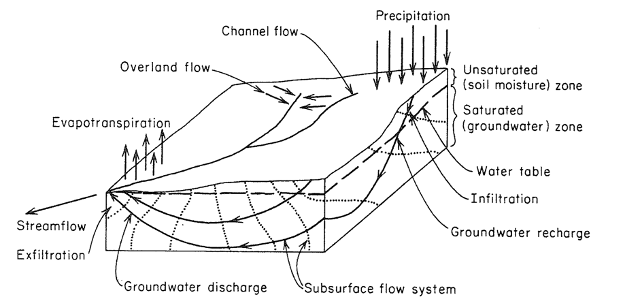

Surface water and groundwater are connected because water moves through the hydrologic cycle.[1] Specifically, water evaporates from the earth’s surface, and then as relative humidity increases, water condenses and falls back to the earth as precipitation. Some of that precipitation evaporates back into the atmosphere, is absorbed by plants, becomes surface runoff, or percolates into the ground (now identified as groundwater) in a process called recharge. Importantly in some areas, groundwater actually moves into rivers and streams, through a process called discharge. Some of this groundwater that discharges into the stream can then again evaporate into the atmosphere and continue moving through the hydrologic cycle.

Freeze & Cherry Fig. 1.1.png

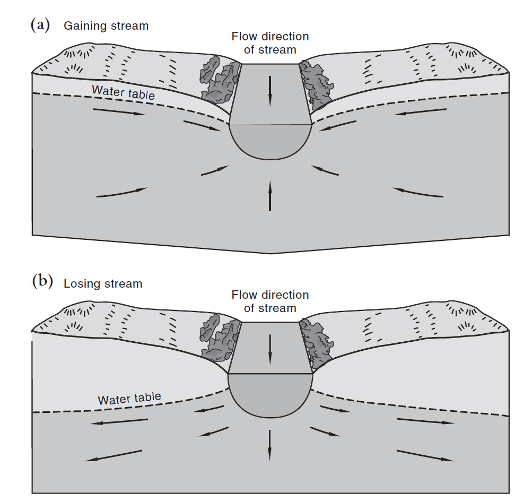

As prominent water law scholar Robert Glennon—himself a longtime collaborator of the pioneering groundwater hydrologist, Professor Thomas Maddock, III—aptly notes, it is evident that as water moves through the hydrologic cycle “[g]roundwater may become surface water [discharge] in some portions of a stream, and surface water may become groundwater [recharge] in other portions.”[2] Humans have the ability impact these natural processes of discharge and recharge when they start pumping groundwater. Specifically, well pumping lowers groundwater levels which, in turn, results in decreased discharge [i.e., contribution of flow] from the aquifer into the stream; this is the case in a so-called “gaining” stream, or stretch therefore. Depending on geologic conditions, as in a “losing” reach by contrast, such pumping may increase the stream’s recharge—i.e., flow of water from the stream—to the underlying groundwater system. These interrelated processing unfold until a river runs dry. This is what happened to the Santa Cruz River.

Glennon Fig. 3.3.png

Despite this scientific reality of the interconnectedness of surface water and groundwater, the Arizona Supreme Court has affirmed, in the so-called Gila IV case, the legal distinction between surface and groundwater in Arizona. There is a bifurcated system of water rights in Arizona. Specifically, surface water rights are governed by rules of prior appropriation (i.e., “first in time, first in right”); in contrast, groundwater is governed by the reasonable use doctrine—at least outside of Active Management Areas, such as the case of the San Pedro Basin. This distinction has implications for GSAs because GSAs only consider “waters of a river system and source,” and under Arizona statute, “waters of a river system and source” only include appropriable [water] or water rights under federal law. This means that only state surface water—not groundwater—claims are subject to GSAs in Arizona. An additional complexity in Arizona is that, in addition to surface water, “subflow”—a legal concept applied to “wet” water—is also governed by rules of prior appropriation. Scientifically, subflow is groundwater. While groundwater is generally presumed to be non-appropriable, the Arizona Supreme Court earlier affirmed, in Gila II, that subflow is appropriable because it is “water from the bed of a stream, or from the area immediately adjacent to a stream, and that water is more closely related to the stream than to the surrounding alluvium.” As noted above, however, GSAs also include water rights under federal law.

In contrast to Arizona water law that distinguishes surface water and groundwater, the Arizona Supreme Court in Gila III recognized that federal reserved water rights extend to both surface and groundwater. Further, the Arizona Supreme Court recognized that federal reserved water right holders are subject to greater groundwater protections than holders of surface water rights under state law because federal reserved water rights extend to both surface and groundwater. The Arizona Supreme Court held that “once a federal reservation establishes a reserved right to groundwater, it may invoke federal law to protect its groundwater from subsequent diversion to the extent such protection is necessary to fulfill its reserved right.”

Because federal reserved water rights extend to both surface water and groundwater, the federal reserved right in SPRNCA reserves both the surface and groundwater that is necessary to accomplish the purpose of SPRNCA. In elaborating the purpose of SPRNCA, Congress directed the Secretary of Interior to “manage the conservation area in a manner that conserves, protects, and enhances the riparian area and the aquatic, wildlife, archeological, paleontological, scientific, cultural, educational, and recreational resources of the conservation area.”

While the exact amount of water for SPRNCA has not yet been quantified in the GSA, it is likely that a substantial amount of water will be needed to fulfill the various purposes of SPRNCA. While quantification is pending, it also seems that groundwater pumping in nearby communities should be limited in consideration of the water that is reserved for the purposes of SPRNCA.

But the Arizona Supreme Court rejected this assumption that water reserved for SPRNCA must be protected from groundwater pumping in proposed nearby developments while quantification of the reserved water right is pending. The Arizona Supreme Court held in Silver v. Pueblo Del Sol Water Co., 423 P.3d 348, 359 (Ariz. 2018) that the Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR) does not need to consider the federal reserved water right in SPRNCA in making an adequate water supply designation for a proposed development Tribute in Sierra Vista. In Arizona, a developer must secure an adequate water supply designation from ADWR before the county can approve a new development. Under Arizona law, an adequate water supply requires, (1) a “[s]ufficient groundwater, surface water or effluent of adequate quality [that] will be continuously, legally and physically available to satisfy the water needs of the proposed use for at least one hundred years;” (emphasis added) and (2) that a “financial capability has been demonstrated to construct the water facilities necessary to make the supply of water available for the proposed use.” ADWR gave an adequate water supply designation to Tribute (a proposed development of 7,000 commercial and residential units) that plans to use groundwater to meet the development’s needs, and the development is within five miles of the San Pedro River. However, ADWR did not (and the Arizona Supreme Court affirmed they did not have to) consider the federal reserved water right in SPRNCA when determining whether there would be “sufficient groundwater” to “satisfy the water needs . . . for at least one hundred years.” As a result, a development has been approved in reliance on groundwater that is likely reserved for SPRNCA. This threatens the development’s future water supply because the proposed development has a junior water right, and the United States has a senior water right in SPRNCA. This means that once the federal reserved water right in SPRNCA is quantified, the water needs for SPRNCA must be satisfied before those of the development. Now, both the development and SPRNCA are at risk of not having sufficient water to meet their respective needs.

The Silver decision only extends to unquantified federal reserved water rights. However, because of the pace of the Gila River GSA, it is likely that this federal reserved water right will not be quantified for several years. Meanwhile, developments within the San Pedro watershed can obtain adequate water supply designations without considering the unquantified federal reserved water right in SPRNCA. Thus, this decision clearly threatens the federal reserved water right in SPRNCA which remains to be quantified in the Gila River GSA.

Because of the combination of (1) Arizona’s bifurcated system of water rights, (2) the slow pace of the Gila River GSA, and (3) the Arizona Supreme Court’s decision in Silver to allow ADWR to approve adequate water supply designations for developments without considering unquantified federal reserved water rights, the United States must seek an alternative means outside of the Gila River GSA to protect the federal reserved water right in SPRNCA. Ultimately, this may mean that the United States must assert its federal reserved water right in SPRNCA in the federal courts.

[1] See Allan Freeze and John Cherry, Groundwater 3-4 figs. 1.1-1.2 (1979) (this is a classic text on groundwater/hydrogeology).

[2] Robert Glennon, Water Follies: Groundwater Pumping and the Fate of America’s Fresh Waters 42 (2002).