Fighting Fire with Fire: Proposed Legislation Would Address the Fire Deficit

- The following is the opinion and analysis of the writer.

- Use of this article or any portions thereof requires written permission of the author.

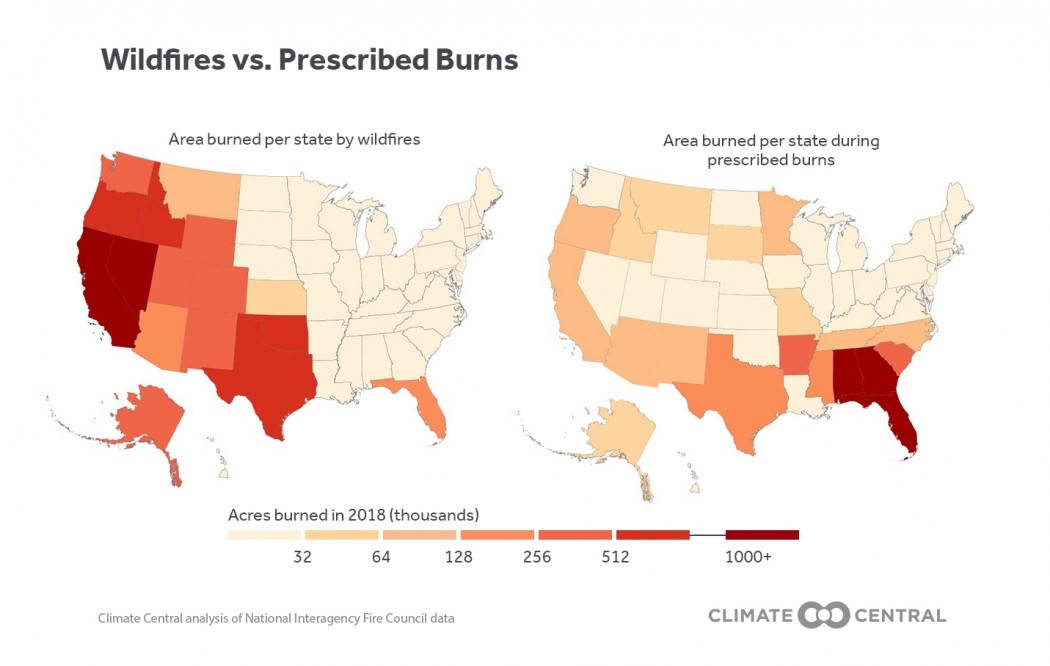

Wildfires vs Prescribed Burns map Climate Central.jpg

Following decades of strict fire suppression, fire managers and policy makers have recently begun to recognize the importance of returning fire to the landscape for multiple resource benefits. Prescribed burning, controlling naturally ignited wildfires, and mechanical thinning are common approaches to reduce fuel loads and protect against high-severity fire. Although there has been increasing recognition of the importance of fire for different ecosystems and a suite of environmental laws and regulations that influence fire management practices for federal land managers, fire restoration in practice has not changed much in recent years (North et al. 2015). About 98% of fires are still rapidly suppressed (Shultz, Thompson, & McCaffrey 2019). Land managers are still prioritizing fire suppression over fire restoration (Climate Central, 2019).

Fire restoration is the act of restoring the natural fire activity in an area through treatments before an unplanned fire or treatments after a fire, including managing a naturally occurring wildfire for resource benefit. Fire restoration actions have to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Air Act, and the Wilderness Act. In addition to legal disincentives, land managers face pressure to put natural fires out and avoid the use of prescribed fires, due to public fear of fire escaping the planned burn area (Franklin, Hagmann, & Urgenson 2014). Any damage done to property during a prescribed burn or managed wildfire puts a land manager at risk for litigation (Kohn 2019).

Meanwhile, land managers do not have to deal with these hurdles if they decide to suppress a wildfire, and it comes with a much higher cost. In the year 2020, federal agencies alone spent $2.3 billion on fire suppression activities (NIFC). In contrast, the chart below shows the amount of money spent on prescribed burning, one type of fire restoration, hovering around $500 million (Climate Central, 2019).

A budgetary mechanism called the wildfire adjustment allows certain fire suppression activities to be “effectively exempt from the discretionary spending limits” (Congressional Research Service, 2020). Fire managers have an essentially open pocketbook when it comes to fire suppression but face annual budgetary restrictions and limitations when it comes to fire restoration.

In 2021, at least three acts have been introduced to Congress that provide for more fire restoration: the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Build Back Better Act, and the National Prescribed Fire Act.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act currently making its way through Congress includes funds to support fire restoration efforts from fiscal years 2022 through 2026. Although there is still a focus on wildfire suppression, the bill uses some of the $3.5 billion dollars to be appropriated for wildland fire programs in the following ways:

- Convert no fewer than 1,000 seasonal wildland firefighters to full-time year-round Wildland Fire Manager positions and reduce hazardous fuels on Federal land at least 800 hours per year.

- $20 million for research conducted under the Joint Fire Science Program.

- $50 million for conducting mechanical thinning and timber harvesting in an ecologically appropriate manner that focuses, to the extent practicable, on small-diameter trees.

- $500 million for the Secretary of Agriculture to award community wildfire defense grants to at-risk communities.

- $500 million for prescribed fires.

- $500 million for developing or improving potential control locations, including installing fuel breaks, with a focus on shaded fuel breaks when ecologically appropriate.

- $200 million for contracting or employing crews of laborers to modify and remove flammable vegetation on Federal land and use the resulting materials, to the extent practicable, to produce biochar, including through the use of the Civilian Climate Corps.

- $200 million for post-fire restoration activities that are implemented not later than 3 years after the date that a wildland fire is contained.

Critics are concerned that efforts to fund thinning projects are just thinly veiled cover for subsidized logging and point out that the end use of the wood as biofuel may be more harmful for the environment than using coal. Proponents identify thinning as a critical part of restoring ecosystem resiliency and recognize that thinning doesn’t just target trees that can be sold as timber (Aton, 2021). Funding projects like biochar give agencies a potential market for the currently unprofitable small wood products of thinning efforts. This bill passed through the Senate on August 10, 2021.

The Build Back Better Act appropriates funds for fiscal year 2022 through September 30, 2031, for management of the National Forest System and other public lands:

- $10 billion for hazardous fuels reduction projects within the wildland-urban interface

- $4 billion for hazardous fuels reduction projects outside of the wildland-urban interface for projects that are noncommercial in nature or, if commercial, ecologically necessary for restoration and enhancement of ecosystems and only limited to small diameter trees or biomass

- $2 billion for vegetation management projects

- $50 million for post-fire recovery

- $2.25 billion for the Civilian Climate Corps

It also aims to appropriate $9 billion in grants for Tribal, state, or other non-federal entities to reduce the risk of wildfire on non-federal land. This act was introduced to Congress in early 2021 and had passed through several committee reviews by September 2021.

In 2020, the National Prescribed Fire Act was introduced to Congress in an attempt to address some of the disincentives and barriers for prescribed fire. The act stalled out last year, but U.S. Senators Joe Manchin, Dianne Feinstein, Maria Cantwell, and Ron Wyden reintroduced it in May, earlier this year.

The National Prescribed Fire Act of 2021:

- Establishes $300 million accounts for both the Forest Service and the Department of the Interior (DOI) to plan, prepare and conduct controlled burns on federal, state and private lands.

- Requires the Forest Service and DOI to increase the number of acres treated with controlled burns.

- Establishes a $10 million collaborative program, based on the successful Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program, to implement controlled burns on county, state and private land at high risk of burning in a wildfire.

- Establishes an incentive program to provide funding to state, county and federal agencies for any large-scale controlled burn.

- Establishes a workforce development program at the Forest Service and DOI to develop, train and hire prescribed fire practitioners, and establishes employment programs for Tribes, veterans, women and those formerly incarcerated.

- Requires state air quality agencies to use current laws and regulations to allow larger controlled burns, and give states more flexibility in winter months to conduct controlled burns that reduce catastrophic smoke events in the summer.

This bill is generally supported by the land management and scientific communities, although some critics point out that not all areas are suitable for prescribed burning, and a combined approach of prescribed burning and mechanical treatments is the most effective. Portions of this bill may be incorporated in similar sections of the other two large infrastructure bills, so it’s likely that passage of the other two would achieve many of the same goals. The Act was read by Congress in May of 2021 and referred to the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources.

Together, these bills allocate around $2 billion annually for fire restoration practices on federal land. According to the National Interagency Fire Council, federal agencies are currently spending about $2.3 billion on fire suppression, so the funding of the fire restoration activities could result in saved expenses. None of these bills have passed yet so it is possible that they may be altered or fail before being enacted. Still, it is encouraging to see attempts to even the playing field between fire restoration and fire suppression.

Managing public lands for ecosystem resilience often means creating a mosaic on the landscape, of mixed-age tree classes and a variety of habitat types for wildlife. Providing land managers with support and incentives to restore the natural fire regime through prescribed fire, mechanical thinning, and other fire restoration practices can help make our forests and our communities more resilient to changing climate and conditions in an uncertain future.

References:

Aton, Adam. (2021, August 11). Could the infrastructure bill make wildfires worse? E&E News.

https://www.eenews.net/articles/could-the-infrastructure-bill-make-wildfires-worse/

Build Back Better Act of 2021, proposed, text:

https://docs.house.gov/meetings/BU/BU00/20210925/114090/BILLS-117pih-BuildBackBetterAct.pdf

Climate Central. (2019). The Burning Solution: Prescribed Burns Unevenly Applied Across U.S. Retrieved from:

https://www.climatecentral.org/news/report-the-burning-solution-prescribed-burns-unevenly-applied-across-us

Congressional Research Service. (2020). Federal Wildfire Management: Ten-Year Funding Trends and Issues (FY2011-FY2020). Retrieved from:

https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R46583.pdf

Franklin, J., Hagmann, K., & Urgenson, L. (2014). Interactions between societal goals and restoration of dry forest landscapes in western North America. Landscape Ecology, 29(10), 1645-1655.

DOI: 10.1007/s10980-014-0077-0

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021, proposed, text: https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/21031186/edw21a09.pdf

Kohn,E. (2019). Wildfire Litigation: Effects on Forest Management and Wildfire Emergency Response. Environmental Law, 48(3).

http://elawreview.org/articles/volume-48/wildfire-litigation-effects-forest-management-wildfire-emergency-response/

National Interagency Fire Consortium. (2020). Suppression Costs. Retrieved from:

https://www.nifc.gov/fire-information/statistics/suppression-costs

National Prescribed Fire Act of 2021, proposed, text:

https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1734/text?r=27&s=1

North, M et al. (2015). Reform forest fire management. Science, 349, 6254, 1280-1281. DOI: 10.1126/science.aab2356

Schultz, C.A., Thompson, M.P., & McCaffrey, S.M. (2019). Forest Service fire management and the elusiveness of change. Fire Ecology, 15, 13.