The Drought Contingency Plan and What It Means for Arizona

- The following is the opinion and analysis of the writer.

- Use of this article or any portions thereof requires written permission of the author.

ricardo-frantz-1042954-unsplash.jpg

On April 8, 2019, the United States House of Representatives and the Senate both passed legislation authorizing the Department of Interior to implement the Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan (DCP). The bills passed with bipartisan support, with all fourteen Senators from the Colorado Basin States cosponsoring the bill. The bill was signed by President Trump on April 17, 2019. Next, the DCP will be signed by the Secretary of Interior and the governors from all seven states in the Colorado River Basin, and then the plan will be implemented.

The finalization of the DCP comes after years of negotiations among the states. The four Upper Basin States, which include Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming, reached an agreement and signed their new DCP in December 2018. The Lower Basin States had a much more contentious road to completion of their part of the DCP. Arizona struggled to meet the federal deadline set by the Bureau of Reclamation because carrying out the Arizona portion of the DCP involves over a dozen separate agreements among all the parties involved – government agencies, water districts, and tribes. California’s Imperial Valley also held up the joint DCP process because its officials there said they would not sign onto the plan without receiving $200 million in federal funding to restore the Salton Sea. However, the Metropolitan Water District, the agency responsible for supplying 19 million Californians with drinking water, said it was willing to assume all of California’s if Lake Mead falls below 1,045 ft. Because Metropolitan is taking over that burden, the Imperial Valley is effectively cut out of the DCP, and the agreement moved forward without the approval of the Imperial Valley officials.

On the same day that President Trump signed the DCP, the Imperial Irrigation District filed a lawsuit in California state court to delay the implementation of the DCP. The lawsuit claims that the Metropolitan Water District violated California's environmental laws because it failed to analyze the impacts of taking greater river water cuts and did not consider how the agency would make up for the shortfall. So far, there is no evidence that this lawsuit will stop the implementation of the DCP.

What is the Drought Contingency Plan (DCP)?

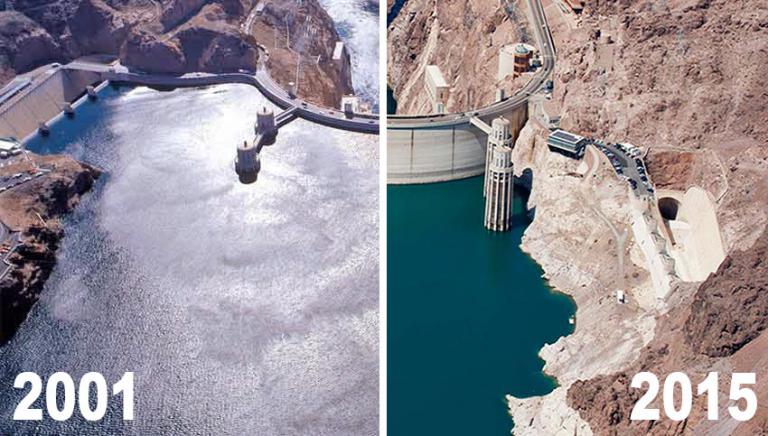

Arizona gets about 40% of its water from the Colorado River, about 2.8 million acre-feet (AF) annually. The state is currently in the midst of a 19-year drought and the levels in Lake Mead, the primary water source for the state, are dangerously close to levels that would trigger cutbacks in the state’s water supply. In 2007, the Colorado Basin States and the federal government agreed to the first DCP, called the “2007 Guidelines,” meant to govern water allotments in the event of a water shortage until 2026. There are three tiers of shortages in the 2007 Guidelines. Tier 1 is triggered if Lake Mead falls below 1,075 ft. If Lake Mead reaches this level, Arizona must cut its Colorado River water supply by 320,000 AF. Tier 2 is triggered if Lake Mead falls below 1,050 ft., in which case Arizona must cut 400,000 AF. Finally, Tier 3 is triggered if Lake Mead falls below 1,025 ft., in which case Arizona must cut its river water supply by 480,000 AF.

The likelihood of a Tier 3 shortage has drastically increased since the original DCP was created in 2007. In 2007, the probability of a Tier 3 shortage was about 8%; now, it is between 30-45% without a new DCP. The idea behind the new DCP is to give up more, concrete quantities of water now before we reach critical shortage levels in order to minimize the risk of losing even more water at unpredictable levels in the future. Lake Mead will almost certainly reach a Tier 1 shortage by the beginning of 2020. Without an updated plan, the Agriculture Excess Pool under the Central Arizona Project (CAP) priority system, which is the water that Pinal County farmers use, would be entirely cut as soon as January 2020.

Under the Tier 1 shortage declaration, Arizona has to cut at least 18% of its Colorado River water usage. Farmers have the most to lose if the DCP is not updated because CAP’s strict water delivery priority system makes them the most vulnerable when the water supply is cut. The cuts are not spread across the users, but instead, lowest priority users lose all of their water before higher priority users are subject to cuts. The Agriculture Excess Pool, created in the 2004 Arizona Water Settlements Act and relied on by Pinal County farmers, is second lowest in priority only to the General Excess Pool. If Arizona must cut its Colorado water supply by 320,000 AF in 2020, as it will almost certainly have to do, these cuts will come directly from the General Excess Pool and the Agriculture Excess Pool, leaving central Arizona farmers high and dry.

What Exactly Does the New DCP Say?

The DCP legislation that was approved on January 31st can be split into two general categories. The first is simple. Under the Arizona Constitution, the Legislature must grant, by concurrent resolution, authority to the Director of the ADWR to sign on to the multi-state DCP on behalf of Arizona. The Legislature granted this authority in its January 31st bill.

Second, the legislation allows for certain water stakeholders in Arizona to make water usage agreements to prevent farmers from shouldering all of the supply cuts. It also authorizes $30 million in appropriations for Lake Mead conservation, $2 million for groundwater conservation, and $9 million for Pinal County infrastructure projects (such as building wells to utilize groundwater instead of CAP water).

Under the new DCP, the cuts in water supply are spread across multiple users, in accordance with three main mechanisms. The first is “mitigation water.” Because the 2007 Guidelines list agriculture as the lowest priority user, farmers and other entities that face cuts will receive mitigation water so the cuts are not as extreme. Right now, farmers in the Agriculture Excess Pool get 275,000 AF of water per year. Without mitigation water, farmers would see that CAP water completely cut under the Tier 1 shortages. Under the new plan, for three years (2020-2022), the farmers using the Agriculture Excess Pool would receive 105,000 AF of water per year. This mitigation water will come from cities that otherwise would have banked the water underground, the private water company EPCOR, and CAP owned water that is currently stored in Lake Mead and Lake Pleasant. Along with the mitigation water, Pinal County will receive funding to build groundwater infrastructure so it can rely less on CAP water in the future.

The next group to face cuts under the DCP is the Non-Indian Agriculture (NIA) pool. This is a misnomer since the primary users of this pool are tribes and cities, namely: the Gila River Indian Community, the Tohono O’odham Tribe, Phoenix, Gilbert, Chandler, Mesa, Glendale, Scottsdale, and Tempe. With the new plan, for two years (2020-2021), users of the NIA pool would get 47,800 AF of mitigation water, with lower amounts allocated for subsequent years.

The second mechanism is monetary compensation to those who contribute some of their allotted water to mitigate the losses of other users. Over the length of the new DCP (2020-2026), the Gila River Indian Community will receive $60 million to forgo most of the NIA water it would otherwise be allotted.

The third mechanism is offsets, which involves trading credit for the water stored in Lake Mead instead of that water being used between different water agencies and other entities. The goal is to leave more water in Lake Mead so that additional cuts will not be needed down the road. In exchange for leaving 10,000 acres of farmland fallow, tribes will receive $30 million over three years. This will result in 150,000 AF of water staying in Lake Mead. The total offsets under the DCP will be 400,000 af over the six years of the plan.

The Bottom Line

The bottom line is the updated DCP, while complicated and dependent on many different factors coming together, is much better for farmers and agriculture communities in Pinal County than the original DCP. Yet while it manages to spread the pain of cuts more evenly under a Tier 1 shortage, either a Tier 2 shortage or a Tier 3 shortage would trigger cuts that affect many more communities. And, once President Trump signs the DCP into law, it will only be in effect until 2026. The planning for a post-2026 agreement for the seven basin states is slated to begin next year.

More information

Water Conservation Plan 2019 - https://arizona.box.com/s/zufdr8fbdfaa50axpxc3jt7vp2v1ww5b

Interview with Bethany Sullivan - https://arizona.box.com/s/ixqi23pj987u2yw4aio9i42w0m1491q0